Ricky Hatton was in a state that was frighteningly removed from the heyday of his career eight months before he returned to the limelight. He weighed 15 stone 4 pounds, was lethargic from drinking on the weekends and eating takeout frequently, and was not only heavier but also emotionally drained. However, something deeply personal was sparked when an unexpected invitation to compete in an exhibition fight against longtime friend and opponent Marco Antonio Barrera arrived.

Hatton wasn’t vying for titles when he accepted the contest. He was taking charge again. It was more than just the ring. It was about motivating those who were silently suffering, whether they were dealing with depression, obesity, or the encroaching weariness of middle age. Notably enhanced by his newfound focus, Hatton tackled the task with an accuracy that made supporters remember the fighter he used to be.

| Full Name | Richard John Hatton |

|---|---|

| Known As | The Hitman, The Pride of Hyde, The People’s Champion |

| Date of Birth | October 6, 1978 |

| Died | September 2025, aged 46 |

| Nationality | British |

| Height | 5 ft 6 in (168 cm) |

| Reach | 65 in (165 cm) |

| Weight Class | Light Welterweight, Welterweight |

| Professional Fights | 48 |

| Record | 45 Wins (32 KOs), 3 Losses |

| Career Span | 1997–2012 (Fighter), Later Promoter & Trainer |

| Hall of Fame Induction | 2024 |

| Reference |

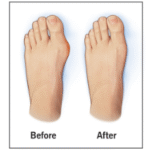

His day-to-day existence changed dramatically. He started eating 400-calorie meals that were preportioned and served with protein shakes. Pub nights and greasy dinners were gone, replaced by a remarkably transparent building. The change was noticeable in a matter of weeks, both physically and emotionally. He gained more time when the July fight was postponed, and by the time it was rescheduled for November, he had lost an incredible four stone. Hatton, who weighed 11 stone 6 pounds, was slender, full of energy, and pleased with his accomplishments.

There was more to this change than meets the eye. Its foundation was emotional recovery. Following his humiliating losses to Pacquiao and Mayweather, Hatton had almost lost his mind due to a mental health crisis. He struggled for years with public mockery, family alienation, and suicidal thoughts. Neither nostalgia nor conceit drove the trip back. It was about demonstrating that, even when the lights go out, there is still hope for personal salvation.

Hatton established a stable environment by carefully regulating his food and abstaining from alcohol. He didn’t give up tea entirely; reducing from eight cups to two was sufficient to keep things in balance without going overboard. Fans, many of whom had experienced their own health-related challenges, responded favorably to this modest, sustainable approach. A middle-aged man once sent him a note that really resonated with him: “If you can do this at 44, then there’s hope for me too.”

Hatton’s narrative is similar to that of other athletes who found emotional healing through physical change. Tyson Fury’s personal comeback, which was also based on weight loss and mental wellness, attracted remarkably comparable attention. Hatton, like Fury, was doubted by both his closest friends and detractors. At first, even his family opposed the notion of an exhibition since they were still troubled by the mental breakdown they had seen. However, as the discipline returned and the weight decreased, their support also did.

There was no official score and no winner in the eight two-minute rounds versus Barrera, but Hatton was clearly transformed. The punches had greater meaning and less force. He had no opponent to contend with. He was facing the past, accepting his own guilt, and encouraging others to think that change is possible.

He talked candidly about the rumors in neighborhood bars, where people made fun of his comeback, thinking it was a desperate attempt to attract attention. “I always enjoyed proving people wrong,” he smirked and said. Once employed to beat champions, same unyielding desire now drove resilience, a kinder, more sustainable objective.

It was an especially novel framing of his comeback. It was marketed as a wellness initiative run by someone who has experienced both adoration and sadness rather than as a sports comeback. His vulnerability had long charmed the British public, who responded with resounding support. In contrast to his professional fights, this incident left only admiration and no controversy.

Socially, Hatton’s metamorphosis came at a period when men’s mental health and midlife reinvention were receiving more attention. In the UK, mental health facilities are overburdened and obesity rates are still high. Hatton’s tale evolved beyond mere tabloid material. It was used as a point of reference in NHS health campaigns, gym posters, and motivating speeches. As a symbol, the image of a 44-year-old man who was previously bloated and broken but was now composed and ready for a punch proved remarkably resilient.

On a professional level, the show also spurred discussions regarding post-retirement transitions among the boxing fraternity. Many combatants withdraw with even less support and less structure. That story was altered by Hatton’s readiness to talk openly about his own descent and ascent. After retirement, trainers, promoters, and fans started to publicly support programs that help fighters emotionally as well as physically.

After the fight, Hatton’s gym in Hyde saw a surge in interest from regular individuals who wanted to drop weight and recover control—not only prospective champions, but postal workers, teachers, and factory workers. He informed one group, “It’s not about belts anymore.” “Regaining a sense of aliveness is the goal.”