Reusable medical equipment is continually moving between patients, settings, and clinical settings, but one rule is always important: every item must be made absolutely safe before being used again. It is not just academic to comprehend the three levels of decontamination; it has a direct impact on infection control results, patient safety, and the legitimacy of healthcare. Decontamination becomes a front-line procedure with significant effects, especially during periods of increased public scrutiny, such as following high-profile infection incidents or during pandemic preparedness.

According to healthcare regulations, decontamination can be a single procedure or a set of related steps intended to render an object safe for reusing. These procedures are required and closely watched, with regulatory inspectors and national organizations keeping an eye on them. Every piece of equipment that enters the body or even comes into contact with weakened skin or mucous membranes needs to go through intricate and meticulous procedures. Although they carry varying degrees of risk, even furniture and pulse oximeters are included in this category.

Three Levels of Decontamination of Reusable Medical Devices

| Level of Decontamination | Risk Category | Typical Equipment | Required Procedure |

|---|---|---|---|

| General Cleaning | Low Risk | IV pumps, beds, floors | Wiping with detergent, hot water and drying |

| Disinfection | Intermediate Risk | Thermometers, commodes | Cleaning followed by chemical or heat disinfection |

| Sterilisation | High Risk | Surgical instruments, catheters | Full decontamination: cleaning, disinfection, sterilisation |

The Department of Health and the NHS provide surprisingly accurate lifecycle descriptions of reusable devices. From acquisition to use, transportation, cleaning, disinfection, drying, inspection, packaging, labeling, sterilisation, tracking, storage, and reuse, it starts with acquisition. Every step has a purpose, and failing to complete even one has been connected to the spread of healthcare-associated infections (HCAIs), some of which have resulted in avoidable deaths.

The UK’s current risk-tiering approach is still based on the 1957-published Spaulding Classification, which is still considered to be very innovative. This model is upheld by the MHRA’s revised Microbiological Advisory Committee guidance. Depending on the type of patient contact, devices are classified as low, intermediate, or high risk.

IV stands, monitors, and bedside trolleys are examples of low-risk devices because they only come into contact with intact skin or stay in the environment. These just need to be cleaned in general. Often, a hot water wipe with detergent and drying is sufficient. This may seem easy, but the cleaning needs to be very thorough and constant. The disinfection chain may be jeopardized by any visible dirt residues that serve as microbial havens.

Commode chairs, reusable bedpans, and ultrasound probes are examples of intermediate-risk devices that come into contact with mucous membranes or are subjected to high microbial loads. Cleaning is just the first step here. The next step is disinfection, which can be UV-based, chemical, or thermal. It’s important to keep in mind, though, that disinfection does not eradicate bacterial spores. Sterilization is therefore necessary for procedures that carry a higher risk.

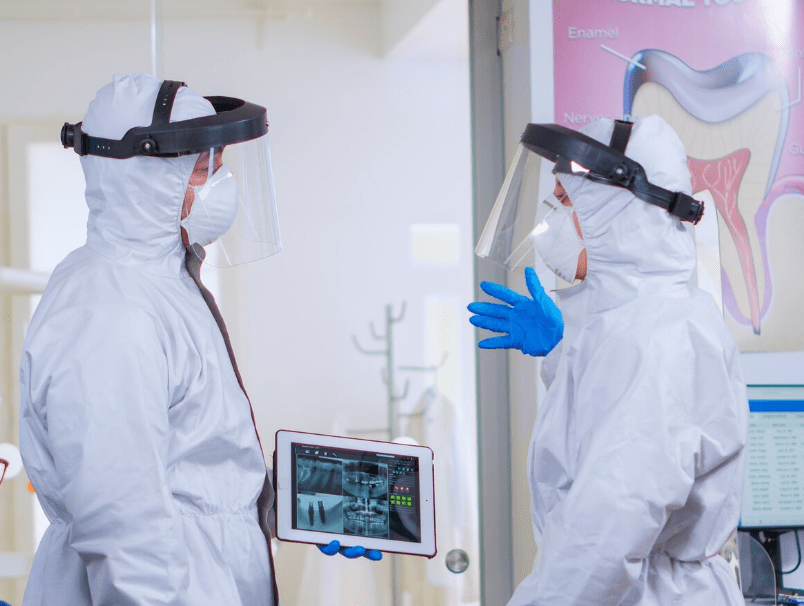

Sterilization, disinfection, and cleaning are all necessary for high-risk devices. These consist of dental scalers, vascular access devices, and surgical instruments. Complete eradication of microbes is required due to their invasive nature. To satisfy these demands, well-known hospitals like Spire Healthcare and The London Clinic have made large investments in sophisticated sterilisation units and automated washer-disinfectors in recent years. In addition to being extremely effective, their procedures are digitally tracked for accountability and audit readiness.

This tiered system is practice-based and implemented in real-time; it is not theoretical. More than 15% of inspected items had insufficient decontamination documentation, according to a recent audit of Birmingham’s handling of surgical equipment. The hospital assigned direct responsibility to a recently hired team of Sterile Services Technicians and instituted QR-code tracking as a corrective measure. Notably, the improvements happened right away. Within six months, that department’s infection complaints decreased by 22%.

Complete sterilisation might not always be possible, such as in mobile field hospitals or during emergency procedures. Clinicians must strike a balance between safety and urgency in this situation, frequently using disposable tools or more intense chemical disinfection. However, these deviations are carefully documented and justified because mistakes can have major consequences, even in emergency situations.

The importance of sterile services personnel is becoming more widely acknowledged. Many hospitals highlight the human effort that goes into creating clean instruments by showcasing the work of their Decontamination Engineers during National Infection Prevention Week. This visibility is essential. Healthcare facilities can emphasize that cleanliness is a promise of care rather than merely a procedure by emotionally connecting with both patients and employees.

Transparency with the public has also improved. Facilities now clearly label cleaned equipment with staff signatures and dates. Patients feel more at ease when they see newly labeled equipment. It adds a level of professional accountability for hospital employees.

A lot of attention was paid to medical-grade decontamination procedures during the COVID-19 pandemic. Hospitals started posting behind-the-scenes photos of their sterilisation rooms and cleaning procedures on social media when public anxieties reached an all-time high. In private clinics where patients pay for every detail, this proactive communication approach was especially helpful in rebuilding public trust.

Even celebrities have voiced their opinions. Influencer Madeleine Shaw and television host Stacey Solomon have shared their experiences with hospital cleanliness during outpatient care and childbirth on social media. Thousands of people left encouraging comments on their social media posts, and some of them even started a discussion about the differences between private and public hygiene standards. The fact that soon after, private wellness clinics started funding public tours of their equipment decontamination facilities is no accident.

Junior physicians and student nurses are now expected to show practical proficiency in cleaning and disinfection procedures during training programs. Practical infection control has become a prominent focus of medical education. Decontamination simulation labs have recently been incorporated into clinical rotations at numerous university hospitals, where students must complete a hygiene audit before beginning patient care.