Even experienced specialists frequently overlook a rare condition like Activated PI3K Delta Syndrome due to its seemingly normal symptoms. Chronic coughs, swollen tonsils, sinus infections, and runny noses are so commonplace that they are rarely cause for concern. These signals, however, are a part of something much more serious for patients with APDS: a basic immune system error that is ingrained in their DNA and frequently misdiagnosed as generic antibody deficiency or CVID.

Genetic variations in either the PIK3CD or PIK3R1 genes cause APDS, which was only recently identified in 2013. These genes are essential for controlling immune cells, especially B and T lymphocytes, which are the body’s attack and surveillance cells. When this pathway breaks down, the body either produces immune responses that go awry and cause inflammation or attack the body’s own tissues, or it produces immature immune cells that are unable to fight infections. The immune dysfunction that results is like a child’s orchestra, with all the instruments present but out of tune, each one attempting to play but failing to produce chords.

| Key Detail | Information |

|---|---|

| Condition Name | Activated PI3K Delta Syndrome (APDS) |

| Discovered | 2013 |

| Genetic Cause | Mutation in PIK3CD or PIK3R1 genes |

| Classification | Primary Immunodeficiency (PI) |

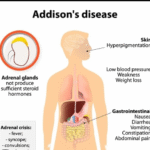

| Common Symptoms | Respiratory infections, chronic cough, lymph node swelling, GI issues |

| Diagnosis | Confirmed via genetic testing |

| Key Treatment | Joenja (leniolisib) – targets PI3K delta hyperactivity |

| Related Risks | Lymphoma, developmental delay, low blood cell counts |

| Inheritance Pattern | Autosomal dominant; can be passed through family lines |

| Reference Website |

Early in life, this immune imbalance manifests itself frequently through recurrent, especially severe infections. Adults may see specialists who treat one system at a time, such as gastroenterology for digestive issues, pulmonology for breathing problems, and ENT for sinus infections, without ever realizing the common thread is immunological. Children with APDS may also be hospitalized frequently. Complications like airway nodules, lymph node swelling, or even lymphoma can worsen undetected because of this fragmented care, which frequently delays an accurate diagnosis by years.

Until recently, managing each symptom separately was the norm. Steroids for autoimmune conditions, immunoglobulin therapy to help failing B-cells, and antivirals for recurrent herpes infections. However, none of these addressed the underlying genetic cause of the actual dysfunction. That changed with the introduction of Joenja (leniolisib), a mechanism-based treatment that recalibrates the defective pathway itself in addition to muting immune dysfunction. That type of intervention is extremely successful in helping people with APDS regain immunological balance and, more importantly, lower their infection rates.

APDS has an emotional and social impact that extends well beyond biology. For parents of impacted children, the cycle of prescription drugs, missed school days, and perplexing explanations frequently feels like an unsolvable puzzle. Before the true cause is found, it is common to misdiagnose asthma, common variable immune deficiency, or even psychosomatic fatigue. The fact that APDS is inherited makes that confusion especially harmful. After a diagnosis is made, testing family members, even those who don’t exhibit symptoms, becomes morally and medically imperative. Parents may learn that they unintentionally transferred the mutation to their children. Silent carriers could be siblings.

The diagnostic landscape has changed as a result of increased accessibility to genetic testing brought about by awareness campaigns and groups such as the Primary Immune Deficiency Foundation. Years of poor management can be transformed into a simplified treatment plan with a single, unambiguous blood test result. However, access to testing is unequal, as is the case with many rare diseases. Support groups like The Assistance Fund become important in this situation. They have greatly lessened the financial strain on already emotionally strained families by providing funding for testing, treatment, and continuing care.

Social media is one platform where the technology promoting this awareness has gained the most traction. Influencers who suffer from invisible diseases, such as primary immunodeficiencies or uncommon autoimmune disorders, are making the diagnostic process more relatable. The emergence of TikTok accounts, where young adults chronicle their lives with conditions similar to APDS, is one notable example. These accounts create an emotional bond that was impossible for traditional clinical brochures to achieve. These accounts have gained a lot of traction in encouraging others to push for more thorough testing when symptoms don’t go away.

Precision immunology, the art of not only identifying diseases based on symptoms but also deciphering them using genetic signatures, is currently the direction of the larger medical trend. This new paradigm is remarkably compatible with APDS. It’s becoming more and more obvious that individualized, root-cause-based approaches must replace the days of symptom management based on trial and error as more diseases are linked to single-gene mutations. That change is marked by Joenja’s arrival. Targeting the precise biochemical “glitch” that causes the illness, it modifies the behavior of a single protein rather than suppressing the immune system as a whole.

This is more than just a scientific accomplishment for patients. It’s a chance to transition from reactive to proactive, long-term wellness. Now, a child who previously missed school every three weeks because of infections can grow up in stability. An adult who previously believed that their weariness was caused by stress can now realize that their immune system was just overburdened and underpowered.

Nevertheless, daily attention to detail is still necessary when living with APDS. When it comes to managing a genetic immune disorder, there are no short cuts. Immune monitoring, vaccination planning, routine follow-ups, and occasionally lifestyle changes are still crucial. However, it is impossible to overestimate the psychological change from confusion to clarity. For the first time, patients have tools that can truly fight back, and they are aware of what they are up against.

The value of listening to patients, particularly those who don’t fit the textbook, is the social lesson that APDS emphasizes. When someone has recurring, seemingly minor infections, is chronically tired, or does not respond well to standard treatment, the solution may lie in a broad understanding of genetics rather than the narrow perspective of a specialist. The way pediatricians, internists, and even emergency room physicians perceive recurrent infections is already shifting as a result of this shift in perspective.