Related Information Table

| Detail | Description |

|---|---|

| Series Name | The Bobbsey Twins |

| First Published | 1904 |

| Publisher | Stratemeyer Syndicate |

| Author (Pseudonym) | Laura Lee Hope |

| Key Characters | Bert, Nan, Freddie, Flossie Bobbsey |

| Setting | Lakeport, USA (fictional); real cities included later |

| Genre | Children’s Fiction / Juvenile Mystery |

| Total Original Books | 72 (1904–1979) |

| Rewrites & Revamps | 1960s rewrites; “The New Bobbsey Twins” series (1987–1992) |

| Cultural Reference | https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bobbsey_Twins |

For almost a century, the Bobbsey Twins captivated young readers’ attention by chronicling gentle adventures with an honesty that often echoed subtly through childhood memories rather than shouting. The stories, which were first published in 1904 under the name Laura Lee Hope, featured straightforward riddles, wholesome investigation, and the endearing relationship of two sets of fraternal twins navigating various facets of American life. In contrast to more extravagant figures like Nancy Drew or the Hardy Boys, the Bobbseys personified something especially timeless: the joy of everyday exploration, frequently depicted through summertime, comfortable porches, or low-key getaways.

The Bobbsey brand was well-known by the 1950s, when television began to dominate American families. However, their emotional nuance was what made them so effective in their reach. Their plots, which were written in a tone that felt especially comforting, concentrated on smaller mysteries—lost pets, strange neighbors, forgotten treasures—instead of pursuing high-stakes suspense. These characteristics have turned into a nostalgic touchstone in recent decades, both for collectors and academics researching the origins of serialized youth fiction.

A group of writers, all of whom contributed their voices while staying mostly anonymous to readers, stood behind the pseudonym Laura Lee Hope. In order to adapt the series to changing reader tastes, later contributors like Andrew Svenson added more structured mysteries, while Lilian Garis, one of the most prolific, gave early editions a poetic domesticity. Like a swarm of diligent bees, these ghostwriters remained consistent over decades, an organizational achievement that is remarkably resilient in literary history.

The structure of all the Bobbsey stories is remarkably similar. Every book followed the same pattern: problem was presented, a light investigation was conducted, and a resolution was reached, usually with a celebration or picnic. Readers felt emotionally safe as a result of the repetition, which was especially helpful for younger audiences who find comfort in predictability. The Bobbsey format has been reexamined as an early example of trustworthy story scaffolding during the last ten years as educational theorists consider narrative structure in early childhood development.

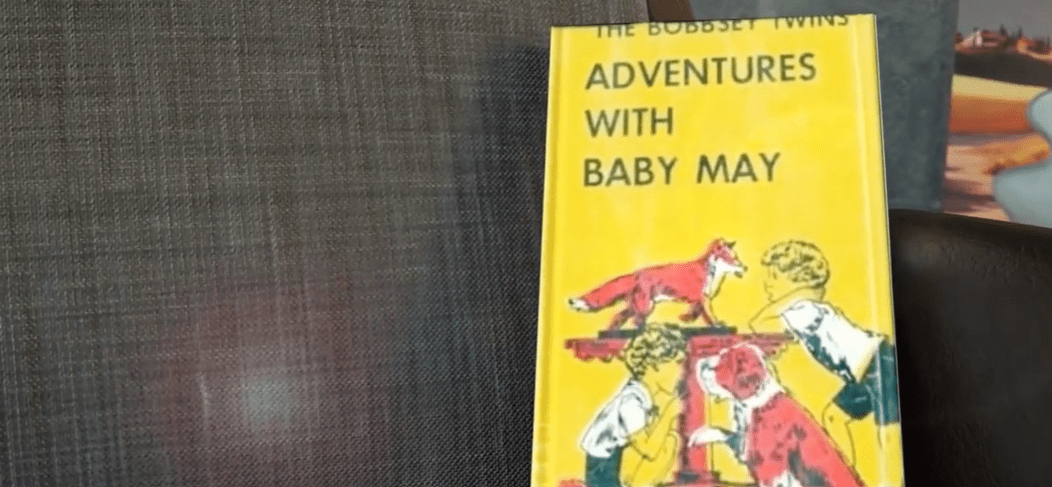

The series was significantly updated in the 1960s to update its tone and fix out-of-date depictions. These changes were more than just aesthetic. In order to make the books more approachable for younger readers, they changed entire plots and substituted outdated language. The Bobbsey Twins and Baby May, for example, was rewritten to include a baby elephant and a baseball team after originally telling a heartwarming story about an abandoned infant. This remarkably adaptable change speaks more to shifting cultural tastes than to editorial whims.

Some of these rewrites were especially creative; they subtly eliminated offensive stereotypes without disrupting the plot. The family’s Black housekeepers, Dinah and Sam, were originally depicted using inflated dialects that were indicative of the prejudices prevalent at the time. Though not totally free from the hierarchical constraints that are still prevalent in mid-century fiction, their roles were reimagined in the 1970s in a more respectful manner. Despite its unevenness, this evolution was a step toward awareness, and it came decades before modern sensitivity editing.

The Bobbsey Twins are situated at the nexus of familiarity and adaptability in serialized fiction. Their tales focused more on the constant assurance that most issues could be resolved by kindness, reason, and good-hearted curiosity than they did on character development. Remarkably, this formula survived two world wars, the Great Depression, Prohibition, and the emergence of television—no small accomplishment for a show that never sought out trends.

The setting changed to suburban shopping centers, aircraft, and even Disneyland in 1987 when a new wave of titles appeared under the New Bobbsey Twins banner. The main appeal of these more recent stories remained the same: kids solving doable problems while remaining distinctly kid-like, despite being much faster-paced and having much better scene variety. The authors were able to modernize without sacrificing the essential tone by using clever plotting.

Through their appearance as complex, modern characters with incisive dialogue and darker plotlines in the CW’s Nancy Drew series, the Bobbsey Twins even quietly made a comeback into popular culture. Their inclusion serves as an example of how flexible, given new context, even the most delicate legacies can become. These characters had changed from who they had been before, but their names had meaning, and that recognition was strong enough to support further development.

The Bobbseys served as introductions to narrative logic and fundamental detective work for early readers. Through familiar settings, they encouraged imagination, demonstrated the value of patience, and set an example of sibling cooperation. These kinds of stories continue to be very effective teaching resources for basic reasoning in the field of early education. Bobbsey stories rooted their readers in a childhood that prioritized community over conquest, in contrast to contemporary fiction that is fixated on dystopian clichés or fantasy warfare.

They didn’t drastically decline. It happened gradually, like a screen gradually taking the place of a beloved rocking chair. However, their cultural influence is still present in resale stores, old libraries, and unspoken allusions. Many people find that coming across a worn Bobbsey spine on a shelf is like listening to a long-forgotten tune—one that is surprisingly low in emotional investment but high in memory.